BACK

The eGlove - When the Mouse Leaves the Desk

0 m

0 words

I worked on this project with Adonis Garcia and Jayden Senior, which explains where the name JAM came from.

An Input Device for Arthritis Patients?

It started with a very specific type of person in mind: the person with arthritic hands, staring at a computer they know how to use but physically struggle with. A conventional mouse asks a lot from the body in very particular ways. It demands a steady wrist, a pinching grip, and small, precise clicks over and over again.

We read about how those repetitive, fine-motor movements aggravate pain for people with arthritis and other hand conditions, and it matched the stories we already knew from family and older adults around us.

Our first design conversations were more about the human body than about electronics. We listed all the usual computer inputs:

Mouse

Trackpad

Keyboard

Touchscreen

Game controller

…and asked a simple question:

What would be easier for a stiff, aching hand?

A trackpad still demands steady finger control. Keyboards aren’t pointing devices. Touchscreens reduce the intermediary device, but they introduce arm fatigue and require you to reach out to the screen.

We kept coming back to a different idea:

What if we didn’t ask the fingers to pinch at all?

What if we let the whole hand move more freely, and moved the sensing away from the fingertips?

Enter the Glove

That’s where the glove came in. A glove is familiar. It’s something you already wear to stay warm or to do work. Conceptually, it allowed us to imagine the hand as a whole, not just the part that pinches a mouse.

The early sketch was almost naïve in its simplicity:

You put on a glove, raise your hand in front of your laptop, and the cursor follows your hand in space.

When you flex a finger, the computer hears a “click.”

The first problem was identified: How do we make the computer “see” and “hear” those gestures with only the tools a first-year engineering lab actually has?

Teaching the Computer to “See” the Hand

We decided to use something each laptop already has: a webcam. We cobbled together a quick OpenCV script that detected a bright patch of color in the camera frame and tracked its center. That colored patch went on the back of the glove.

For a while, it felt like a silly toy. Watching the blob bounce around the screen was kind of neat but ultimately pointless. Then we hooked it into the cursor, and it all became real. It jerked and jittered, and sometimes flew to the corner of the screen for no obvious reason.

That jitter was my first real lesson in embodied interaction:

To the computer, a little noise in the coordinate stream was acceptable;

to a person trying to move a cursor, it felt like the machine was ignoring them.

We spent an embarrassing amount of time tweaking HSV ranges and smoothing functions, not because an assignment said “optimize tracking” but because it just didn’t feel right yet.

Rethinking “Click”

Clicking proved to be more philosophically interesting than we’d anticipated. Mice and trackpads are optimized for fast, shallow clicking, which is exactly what hurts many people with arthritic joints.

We brainstormed all the fancy options:

Flex sensors sewn into the glove

Pressure sensors in the palm

The sci-fi fantasy of muscle-signal (EMG) sensing

Flex sensors were fragile and expensive, and EMG was well beyond our technical level. So we ended up with something incredibly low-tech: rings, strings, and a microswitch.

We printed small plastic rings that slid onto your fingers. Each ring had a tiny channel where a string could be tied. When you bent your finger, the ring rotated, the string tightened, and somewhere on your wrist a switch went “click.”

Can you tell where the ring is? 👀

Sketch of Nano board

That string stretches down to the microswitch so that a small leads to a click

The wrist housing for the electronics included:

Arduino Nano: the main microcontroller, mounted on a small perfboard, reading the microswitch inputs and turning them into clean digital events (with a bit of debouncing).

Bluetooth module: a small board fixed near the outer wall of the housing responsible for streaming click events wirelessly to the laptop.

Battery and power circuit: a compact rechargeable battery, a simple charging / protection board, and an on/off switch. Most of the mechanical design work here was about placing this weight so it hugged the forearm instead of feeling like a lump hanging off one side.

Microswitch row + wiring harness: a line of tiny pushbuttons mounted inside the housing, each tied to one of the finger rings via string, and some thin wires routed through strain-relief holes so the “clicking” motion doesn’t yank connectors loose.

Those rings were my favorite kind of design problem. They were a mix of anatomy and mechanics.

Place the string hole too high, and the string digs into the finger.

Place it too low, and it barely moves when the finger bends.

The ring has to be thick enough to hold a knot, yet thin enough to be comfortable.

Designing them meant thinking in millimeters and in bodies at the same time:

How does a knuckle move?

What does it feel like to bend a stiff finger?

Where does plastic rub against skin after five minutes instead of five seconds?

The Tech Chain

We wired the rings and strings up to tiny pushbuttons inside the wrist housing. The microcontroller watched those buttons, and when they changed, it sent simple signals over Bluetooth.

On the laptop side:

Another microcontroller listened → It passed those signals to the Python program → The program turned them into left clicks, right clicks, or scroll events. This box was the champion behind all of this:

Inside that box was this circuitry that my friend Adonis made using Fritzing. It implemented an LED system in the receiver circuitry that turned on one LED when powered, and another when the glove was connected to the receiver.

This might sound straigforward, but in practice, this chain was brittle:

A string that was too slack meant you could bend your finger and nothing would happen

A missing resistor on the button meant phantom clicks appeared out of nowhere

A flaky Bluetooth connection meant the entire experience would freeze for a second, then come back, breaking your trust every time

On an ordinary gadget, that’s annoying. On something that calls itself “assistive,” that’s unforgivable. That tension made me much less casual about phrases like “It mostly works.”

The Hard Question: Would This Actually Help?

By the time we had a semi-stable prototype, we started asking a harder question:

Would someone with arthritis actually prefer this to a mouse?

The honest answer is probably:

“Sometimes, but not often enough yet.”

The glove removes the need to pinch and drag a device on a desk, but it doesn’t remove the need for effort. The user now has to:

Hold their arm up in front of a camera for extended periods

Flex fingers against strings

Tolerate an object strapped to their forearm

For some people whose main problem is pinch grip and fine clicking, that trade might be acceptable. For many others, especially those with shoulder pain or generalized joint stiffness, it could feel even worse.

Plus, we had never actually tested with people who had arthritis, only classmates with healthy hands and curious minds. The more we sat with that, the clearer it became that describing the eGlove as:

“a better device for people with arthritis”

…would be, at best, wishful thinking.

Reframing the Project

That realization forced a pivot in how I understood the project. If this wasn’t a solution for arthritic hands, what problem were we actually exploring?

The answer we came to was less medical and more about interaction:

Most pointing devices assume a flat surface, a steady wrist, and a tight grip.

The eGlove is really a probe into a different paradigm:

A low-cost, surface-free, wearable pointing device

Driven by gross hand motion and simple finger gestures

The important shift was from:

“this will help people with arthritis”

to

“this shows one way the mouse might leave the desk.”

It’s still motivated by empathy, but it’s honest about being the beginning of an idea, not the end.

Watching People Play

Interestingly, that reframing didn’t come from a whiteboard; it came from watching how people behaved during demos.

When we let classmates try the glove, no one quietly opened a spreadsheet. They started playing:

Tracing big shapes in the air

Trying to “paint” with the cursor

Asking if they could use it to control a simple browser game

The movement felt inherently a bit theatrical: instead of a tiny wrist twitch, you were moving your whole hand. That read more like a game controller or a Wii remote than a productivity tool.

It belatedly dawned on us that eGlove might be better positioned, at least in the short term, as a playful, embodied controller for casual or party games and motion-based experiences. For those scenarios, the “flaws” of mid-air input—big gestures, imprecise pointing, dramatic overshoot—are features, not bugs.

Ethics of Assistive Design (AKA: Good Intentions Are Not Enough)

Beneath the technical story, eGlove served as a small crash course in the ethics of assistive design for me.

It showed me that:

You don’t get to call something “accessible” just because you meant well, and it compiled.

If people in your target user group haven’t:

Worn it

Complained about it

Broken it

Told you where it hurts

…your design is still a hypothesis.

It also made me much more aware that changing an input device doesn’t remove effort; it redistributes it across other joints, muscles, and postures. Every time we moved a string attachment point or sanded a sharp edge off the housing, we were quietly deciding which other part of the body should work harder.

If I Picked Up eGlove Again

If I were to take up eGlove again, I would follow two parallel paths.

1. A genuinely assistive path

I made a terrible mistake: we preached for arthritis patients, yet we didn’t include them in the design process at all. We just assumed our product would be helpful. That’s why, if there is a next time, I would:

Co-design sessions with people who suffer from arthritis or tremors

Build prototypes around the specific movements they find easiest and safest

Expect the result to look very different from the first-year glove

2. A playful, game-focused path

The fact that people instinctively treated it as a toy was a valuable piece of user research in itself. So, I would want to explore how we can

Design a simple rhythm or drawing game where hand gestures are delightful rather than fatiguing

Explore use as:

A prop in a party game

A fun controller for casual motion-based interactions

A secondary input for streamers (triggering emotes or overlays with a flick, maybe?)

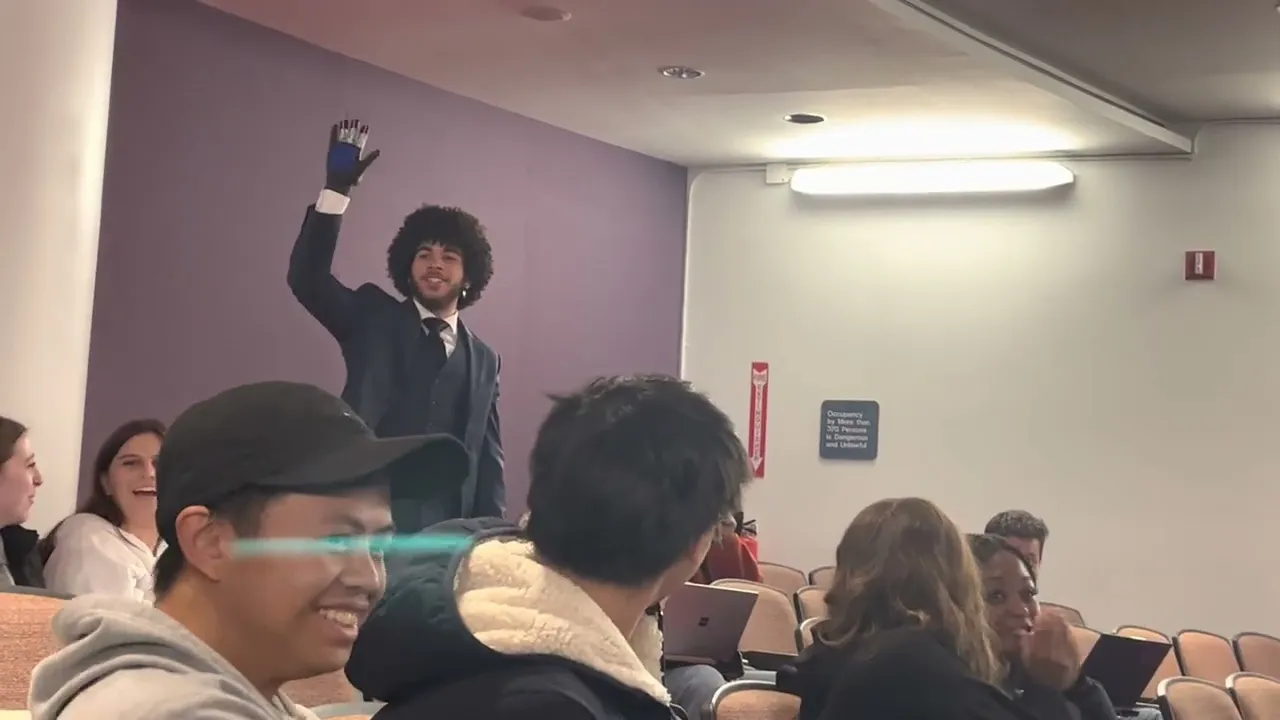

If you’re interested, here’s our final pitch at NYU’s design showcase competition. We won Top 7!